By Mikaele Foley

Tahitian artist Eriki Marchand, who worked at the Polynesian Cultural Center from 1988–‘93, returned to Laie for several months in mid-2024 to design and install a new mixed-media mural in the Courtyard Marriott Laie north shore hotel that marks the sesquicentennial of Hawaii King Kalākaua’s 1874 visit to this community.

In the first year of the Merrie Monarch’s reign (from 1874–1891), King Kalākaua and Queen Kapi’olani selected Laie as the destination of their first royal visit to recognize the community’s thriving commitment to preserving Hawaiian language, culture, and future generations.

One hundred and fifty years later, Marchand’s new mural pays tribute to that visit and Laie’s royal ties. The king and queen also made several subsequent visits to Laie during their reign.

Successful silk-screen artist and businessman: Eriki, who is of Tahitian/Marquesan/French ancestry, grew up in Papeete, taught himself art in those early years, started to learn English from the American missionaries and served his own church mission in his home islands in the late 1970s.

Then he married Patricia Teatareva, whose ancestry traces back to Tahiti’s Tuamotu islands, and he used his self-taught artistic talents to establish and successfully run a tee shirt silk-screening business in Papeete.

At age 31, Eriki said he was inspired in a dream to continue his studies. “We had a very successful business, and so, when I decided to sell everything and move here, most people thought I was crazy,” he said. “But how could I resist when I heard the ‘call’? I said I’ll obey, and it was a great experience.”

Though more mature than most, like thousands of BYU–Hawaii students before and since, Eriki enrolled at BYU–Hawaii from 1988–’94 as a fine arts major. His wife and their two young children accompanied him, and like many other student couples, another child joined the family during the years they lived in TVA.

In school, Eriki focused on three-dimensional art under the late Professor Jan Fisher, with whom he worked on the famous Duke Kahanamoku statue on Waikiki Beach. He also quickly secured a student job in the Polynesian Cultural Center’s graphics department, working with the late Wilma Fonoimoana and Chuck Rivers.

Full-time student and student-manager: In addition to his studies and work at the PCC, Eriki noted he also served in several student ward bishoprics. “I was very busy,” he said.

“After I worked in graphics for one year, I received another dream,” Eriki said, in which three men told him to quit his job there and go work in the Marquesas compound.

The PCC added its Marquesan tohua — or ceremonial platform — during the mid-1970s expansion, and initially positioned it as a Polynesian “ghost town.” Eriki explained this was partially because the dense population of the once thriving island archipelago — located about 750 miles (about 1,200 km) northeast of Tahiti, had been the main source of immigrant Polynesians to Hawaii centuries ago, while its modern population had dropped as low as about 2,000 people at one time, and is currently about 9,500.

Still a BYUH student, Eriki was soon named the full-time Marquesas manager, and with his artistic skills and cultural heritage with those islands, he began making dramatic changes, “bringing new life not only in the compound but to the Tahitian Village as well. The Marquesas became a ‘real PCC village’ in its own right,” he said.

For example, the beautiful feather headdresses, costume changes, and tattoos Eriki created were soon featured in visitor media and PCC advertising around the world. Former PCC sales managers also remember packing a life-sized photo-cutout of Eriki in full Marquesan regalia to various trade shows. Millions of visitors enjoyed the new programming, including pig hunting and wedding dances, as well as other changes in the Marquesas, which also inspired other villages to be more creative.

The graduate returns to Tahiti: “Right after my graduation, we went back to Tahiti, and I began teaching art and wood carving in the high school as my main career. I still live in Papeete and the nearby district of Toahutu, but I retired from teaching seven years ago,” Eriki said.

However, he’s also still a freelance artist in demand. For example, he’s become a specialist in creating unu — a type of tall Tahitian totem pole. “I carved three of these monuments out of mahogany for the anti-nuclear tests back in Tahiti,” Eriki noted, “and I did the most recent one for the big wave at Teahupoo, where they held the 2024 Olympics surfing competition.”

Long-time friend Christian Wilson, who continues to operate his late wife’s gift kiosk in the Hukilau Marketplace, pointed out the Church also commissioned Eriki to create a painting of the arrival of the first Latter-day Saint missionaries in what is now known as French Polynesia in 1844 [with an appropriate site to hang it still to be determined]. And, of course, he still creates designs to help his wife, who now runs the tee shirt silk screening operation. “But she’s my boss,” Eriki insists.

“The Hope of a King” mural: Which brings us to earlier in 2024, when the Courtyard Oahu North Shore issued an RFP — request for proposals — to create an approximately 18-by-10-foot mural to be installed near the hotel’s elevator of the hotel commemorating King Kalākaua’s first visit to Laie 150 years ago.

During his reign from 1874 to his death in 1891, King Kalākaua soon became known for his commitment to help preserve Hawaiian culture. For example, he was given the nickname the Merrie Monarch, and today his namesake hula festival’s website notes that King Kalākaua and his queen Kapi‘olani, even “after many decades under [some] Christian missionary teachings, [in which] Hawaiian beliefs and traditions were suppressed, …did not support such teachings, and instead …lived by the motto, Ho‘oūlu Lāhui, Increase the Nation. He advocated for a renewed sense of pride in all things Hawaiian.”

Christian Wilson encouraged Eriki to submit a proposal, and after two months of research and sketching, a hotel advisory panel selected his design for the mural, which is scheduled to be unveiled on September 25th.

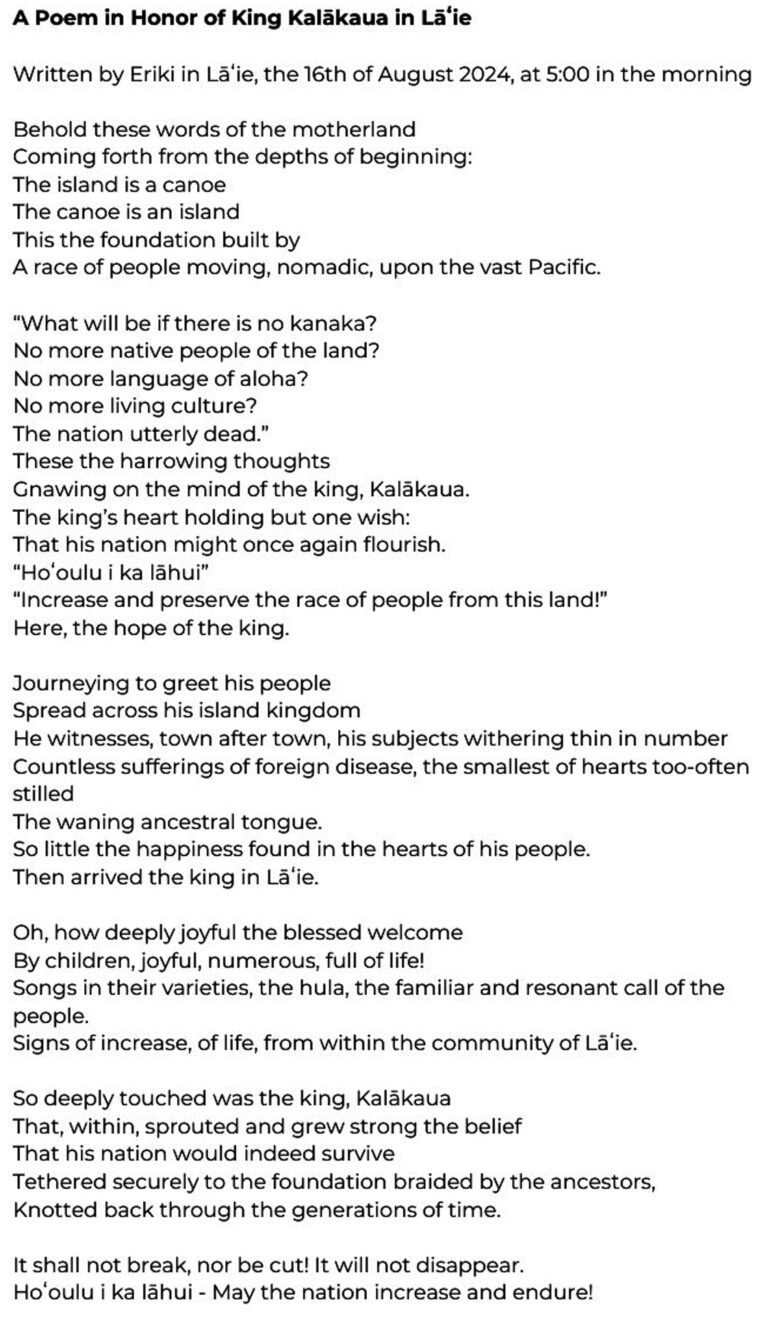

Eriki explained the tentative title for the mural is “The Hope of a King” and includes painting and wood carving elements. His design depicts the king’s party arriving in Laie — with the royal yacht in the background at Laie’s pier [pilings of which can still be seen in the water] and a canoe in the foreground at Pahumoa [the traditional Hawaiian name for the area popularly known as Pounders Beach].

Eriki’s sketches also show his majesty’s delight at seeing all the children in Laie, Hawaiian being spoken, and people openly teaching and learning hula — all this at a time when, like their Marquesan “cousins,” the population of native Hawaiians had begun to diminish.

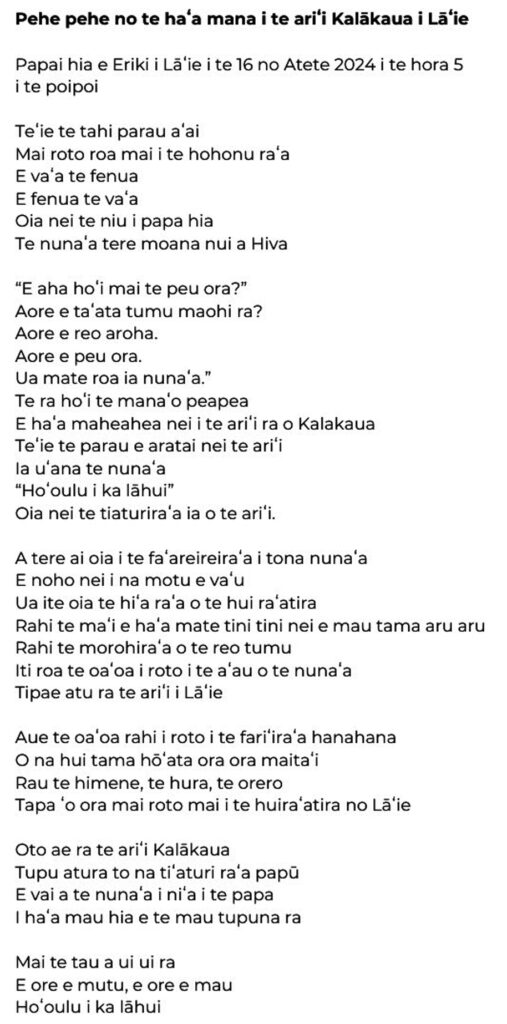

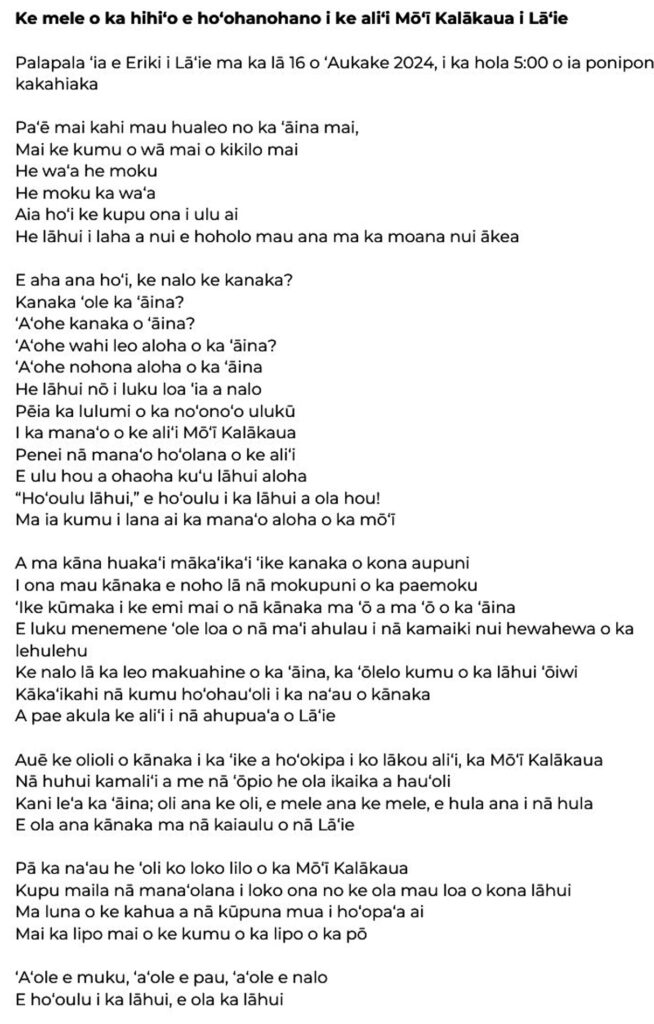

“I had another dream [in August 2024], after which I wrote a poem on the artwork in Tahitian,” Eriki said. “Kamoa’e Walk is translating it into Hawaiian and English, which will be posted by the mural.”

Maybe the mo’opuna: Finally, Eriki said none of his three children have attended BYU–Hawaii, but he’s hopeful that some of his grandchildren might come some day.

And, he added that even today he would still like to “build a bridge between the Marquesas and BYU–Hawaii” so more students from there could come to the Center. “Education is the key,” he said.

September 25, 2024 • Laie, Hawaii

In unveiling the new mural, Eriki acknowledged many people — quite a few of whom are also Polynesian Cultural Center alumni — who helped make the commission possible and supported him, including:

The owners and others affiliated with Laie Ventures LLC, dba Courtyard by Marriott Ohau North Shore and the Marriott organization; David Betham, the hotel manager; Kela Miller, the hotel’s Hawaiian cultural specialist who, “despite significant challenges, deeply inspired this work,” Eriki said.

Also, Micah Casey, assistant manager, and Lana Casey “for their cultural guidance”; Tui‘one Pulotu for providing the wood; Tommy and Jared Pere for preparing and transporting the wood as well as supplying the tools; Chuck Andrus and Kawika Eskaran, shaping, polishing and gluing the wood; Cy Bridges “for his insights on cultural and historical details”; Tama and Gailyn Bopp and the BYU–Hawaii Archives for research on King Kalākaua’s visit; and Iona and Elisa Teriipaia, and Etua Tahauri for ongoing support.

“I’d also like to thank my family and friends for their unwavering encouragement throughout my career. Without their love and belief in me, I wouldn’t be standing here today. To my fellow artists and creatives, thank you for inspiring me daily and reminding me that art is not only about the final product, but about the journey of creation.

“I hope this artwork brings you as much joy and inspiration as it brought me while creating it.”

A vision “during the first week of creating this piece”:

Eriki also shared a “300-word poem in Tahitian” that came to him “in a dream during the first week of creating this piece. I woke up and and wrote it down immediately. My dear friends Kamoa‘e Walk and Tama and Gailyn Enos Bopp translated it into Hawaiian and English [respectively], so I could share its significance with you…”

“I hope that every guest who views this artwork finds their own connection to it — whether that’s a sense of peace, wonder, or reflection. The faces you see depicted are of key figures in our community — people who have dedicated their lives to preserving Hawaiian culture, music, language, and history.”

“These include Mary Kawena Puku‘i, Cy Bridges, Kela Miller, her great-grandparents, Sally Wood Nalua‘i, Sunday Mariteragi, Keith Awai, Ellen-Gay Dela Rosa, Harry and Donna Brown, Bill Wallace, and countless others who have inspired this piece.”

Your comment has been submitted for administrator approval.

Your comment was not saved. Please try again.

No comments yet.