[Interview by Nina Jones]

“…A fantasy that someday I could be doing this…”

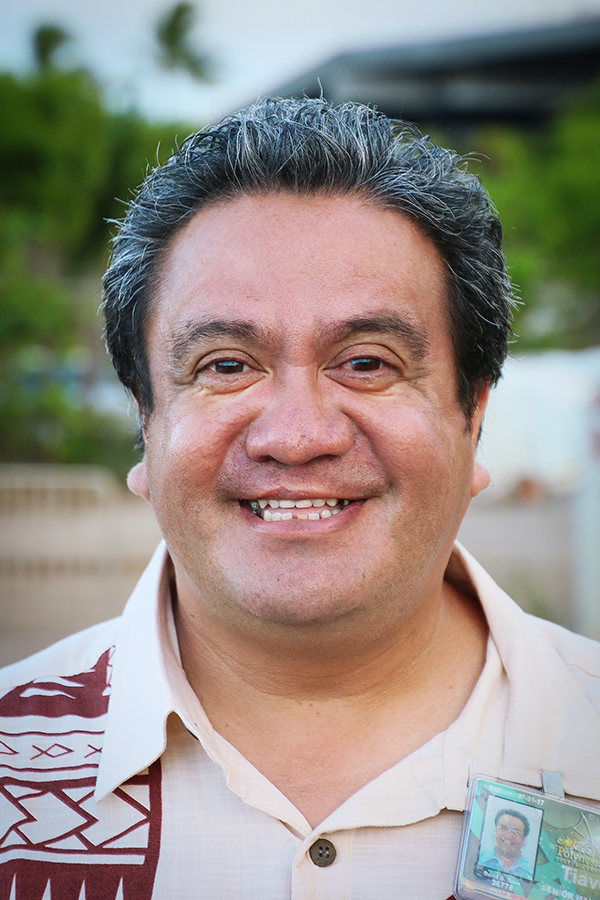

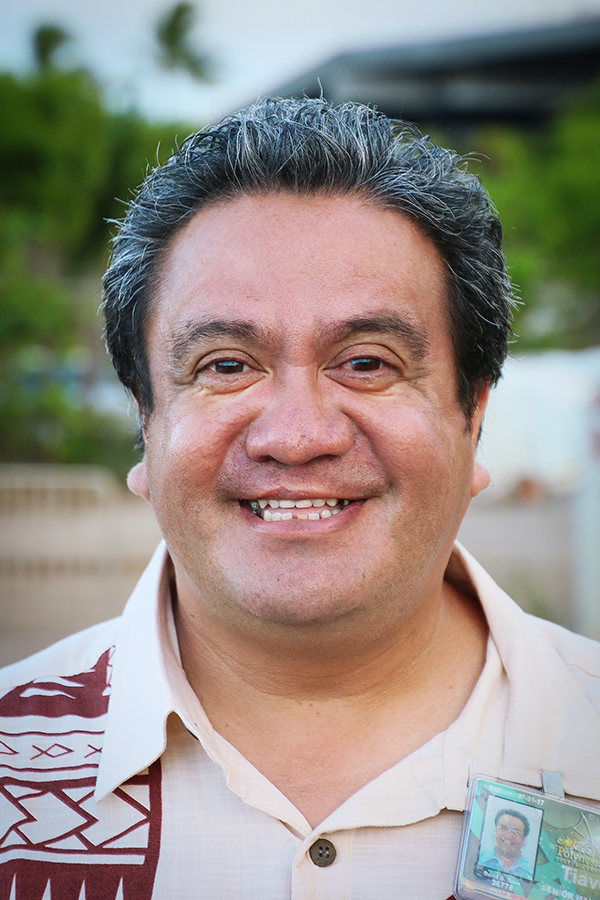

Q: Kavika, tell us about your background at the Polynesian Cultural Center, please.

A: I started here, I believe, in August 1985, right out of Farrington High School in Honolulu. But before then, when I was still at Farrington, I really loved coming to Laie and watching the night show.

When I finally began attending BYU–Hawaii for a couple semesters, my first job at the Center was working in the Gateway Restaurant as a busboy, then I was promoted to the food line. While I was there, Food and Beverage was one big department, and during night show intermissions, we sold pineapple deelites.

That’s when I saw the opening of the new night show, This is Polynesia, and I was blown away.

While at BYUH, I would always sneak into the night show. I decided I wanted to be a part of it, but it wasn’t as easy as they made it out to be when they said, “Just go and audition.” I had to audition five times.

At that time each culture [i.e., night show section] had its own instructor. Samoans, for example, were under Vai Faamaligi, or Auntie Vai. She was very talented, but when I tried out, I knew I was not going to get it.

Next, I tried out for the Tongan section under [Fakasi’i’eiki] “Fasi” Tovo, but I didn’t get that. I didn’t go out for Fiji either, because I knew I wouldn’t get it, but I did try out for Tahiti with Regina Pasi. I didn’t get it. Then it was with Ellen Gay Dela Rosa for Hawaii. Nope.

The instructor who finally hired me was the one everyone said was strict. Uncle Tommy Taurima, the Maori instructor from New Zealand at that time, and he was hard!

Right away, I learned my stuff. I got on stage, and I think within six months, I became his lead dancer. That was hard because I was not Maori, but he chose me, and I got to work closely with all the other instructors who didn’t hire me, and to this day they are my best friends.

A few of them have passed on: Vai Fa’amaligi, the Samoan instructor, Joe Tulele for the Fijians, and Uncle Tommy, but I learned a lot from them. I see a lot of their old-school ways in me. For example, I’m not used to repeating myself three times, “Okay, keep it down, keep it down.” Sometimes the old school comes out like, “Who’s talking? Pay attention when I’m talking! No one talks so you know what to do!”

Now I choreograph, then we run rehearsals and make corrections. With a cast this size, you need someone up there that can call them out. At the same time, there’s a respectful way to do that they can trust. Sometimes they react, “Wow, scolding our line. Gosh”; but after about the third time, it’s more like, “Pay attention or sit down and bring in the next group.”

It’s just really different now compared to when I came in and how I was told. “You, listen.” Now, I respect them, but you’ve got to show more love.

Q: How many performers are in the show now?

A: I would say it’s close to a hundred. They’re not all dancers. We include the tech people in the back. That’s another 10, plus we have lights, audio, and ushers on the crew. So, all of them together comes up to about a hundred.

Q: What are the shows and positions you’ve been involved with?

A: I worked as a dancer for This is Polynesia and Mana! and by the time Horizons: Where the Sea Meets the Sky came around, I had become the stage manager. That was never my goal, more like a fantasy that someday I could be doing this, but I was aware back then managers were highly respected.

Otherwise, I was just dancing and traveling. I’ve been places I’ve never dreamed of. People asked me, “So, you’ve been to Japan?” I go, “Yup, 12 times.” “You’ve been to China?” Yup, five times, and I’ve also been to Colombia and Ecuador — all the places I would never have gone.

I travelled all over the United States when we had promotions with United Airlines. We would fly to all “their” states, usually during the winter, and we’d stand in the lobbies, without a shirt, giving leis as the guests came out of the cold.

By the time Mana! started, our vice president said a stage manager job was coming up. I decided I had to do something, because while working part-time and traveling was good, when I was at home I wasn’t making much. I applied for school and the stage manager job, which I ended up getting. I also got into school, but I thought, “No, I’ve got to make money!”

Since then, I’ve been in different Theater positions. For example, I became the artist and repertoire manager in charge of manpower and hiring, even though I couldn’t say “reper…-what at the time.”

For a while, I took a break from Theater and went to the Marquesas Village. That lasted about six months. Then I went to the Promo Team, full time, but less than a year later, Promo came under Theater, so our promo director was over theater. I ended up being back here.

Q: Why does the Center change its night shows?

A: That’s a good question. This is Polynesia, I think, ran for seven or eight years, and Mana! ran for four or five. Horizon ran longer than 13 years, and our current night show, Hā: Breath of Life, is going on 14, I think.

I found out later that Marketing has a lot to do with requesting changes. It’s not just, “Okay, let’s have a new show.” Of course, money and funds figure in too.

While we were still running Horizons, Dave Warner [director of Church pageants] came to develop Hā. That was the first time I knew of someone from the outside telling us what was going to happen. Hā is so different from all the other shows. It has a storyline that involves acting. The majority of us were like, “No, we can’t act.”

I told you I was blown away when I first saw This is Polynesia, but there were others saying it was too Hollywood. It had a different kind of music. I was like, “Really?” I came in thinking it was the best thing, but I can see how this happens. In this community, they love this place so much they often voice what they feel. Many of them performed here, and they compare with their times. “Oh, back when we did it, we did this. It’s different now.”

When friends come back I used to perform with, they say, “It’s not the same.” It’s not the same because we’re not there. It’s different. It’s the younger students’ time now; and when they come back in the future, they’ll go, “It’s not the same.” Then someday, it will be somebody else’s turn.

David Warner came with two choreographers. One was on Broadway, and one did things for Church pageants. I respect them for what they did, because it’s different. We learned a lot from Warner and his team about acting, about having a story to tell.

And the kids did it. The original Hā cast gave it their all. A good example was when the choreographers told us, “Do this” — dun, dun, dun — or men, don’t dance like this. I said, “Okay, that’s not how we dance. This is how we do it. We end this with our feet apart. Not like this.”

They had good ideas and good staging, but we don’t walk like that. We move into place like that. They told me where they needed us, where we needed to end, and then we came up with the triangle idea in the beginning.

I’m going to be honest, sometimes people say, “It has to be cultural,” but sometimes that can be boring. A long Hawaiian or Tongan chant can be so monotone. That’s culture.

For example, I remember Dave Warner made a comment, “I noticed a lot of them speak to me, but they can’t look at me.” Well, we don’t do that. We show respect. So, he learned cultural things, and we learned so much.

He used terms like, “I need eight counts of this motion to get to here.” For me and Jon Mariteragi, our job at the time was to come up with things to fit, such as the Hā overture before the sail comes down, with that triangle of boys moving. That was done in three minutes. I was making up things. “Just follow,” I said, and I’m not Hawaiian.

I was asked, “What are they wearing?” We cannot just have them in a Samoan costume doing Hawaiian stuff. And they said, “Whatever you want.” Then we figured, it’s the opening. Keep it traditional kahiko (Hawaiian) with all-Hawaiian motions.

Q: How often do you have to audition new dancers?

A: We have auditions whenever we are short. They run throughout the year. For example, when we know there’s a new iWORK [the PCC/BYUH work-study program] group coming in, we hold positions for them. But sometimes they don’t arrive. Other times, they have to understand they’re hired to dance not only their own culture.

Our performers are divided into two groups; Tofisa and Hamata. Tofisa stands for Tonga, Fiji, Samoa. That’s what I’m over. Right under me, I have a supervisor and then two student leads. Hamata — for Hawaii, Maui, Tahiti — that’s Jon (Mariteragi)’s group. He has a supervisor as well.

Q: What are some interesting, unusual things that have happened?

A: Many things have happened: The electricity went off once during Hā.The lights came back on quickly, but not the sound, and it happened during a part of the show when just drums were playing.

The show carried on. The audience didn’t realize we kept drumming because there was no sound; then the sound kicked in suddenly — two seconds before it was time for the musicians to sing.

In another example, at the start of the show, I cringe every night because of the large sail that drops down. When we first started, we had a problem. Just one side came down, so the animation only appeared on the triangle “screens.” Another time when it was supposed to drop down, it was stuck. During the Tonga section, someone had to go up there to fix it.

When Horizons was transitioning to Hā, we had to build a whole new catwalk above the audience, install thousands of lights, and the sail. We didn’t have a truss [lifting and lowering machine] that we could hook it to like now.

During rehearsals one time, we had to go upstairs to the lights, climb up on the roof, come down through a little door, and stand there with this sheet that barely fit. There were four of us up there trying to hold the sail, drop it manually, and haul it up again. Warner said, “Okay, one more time,” and someone had to re-run the whole process.

With the ongoing night show, like most productions, we couldn’t shut down for three months, even though Maintenance was building a revised stage and theater. After the night show, the first three seats by section one, portal one, were removed. Maintenance had this ramp for a cherry-picker [machine] to come on stage. They worked all night from 9 p.m. to about 4 a.m. Then another group came in the next evening and continued the work.

By 4 p.m., the cherry-picker had to leave the theater, so we would prep for the night show. After the show was over, same thing. They worked all night in the theater to make sure we would meet our deadline.

It could be irritating because sometimes the first five rows of seats were covered with a black tarp, so they could fix something. I didn’t know much about it, I just remember seeing it covered.

During our pre-production meetings, we were told, “Okay, section two is closed tonight. And sometimes our lineup kids were still dancing there. We still performed regularly as it was.

Q: Does the audience, who stay dry when it rains, realize performers are getting wet?

A: When it’s rainy and windy, everyone in the theater gets wet, even the audience. If they were getting it lightly, they could still see what was happening on stage, but when it’s windy and the sail drops, we have to be careful with torches because they’re hard to keep burning. However, we still get the biggest standing ovations on nights we have heavy rain.

Another time the power went off, but we continued the show using only torches for lighting. The audience still applauded. They thought that was just the natural look we were going for.

Q: What’s the significance of the fire scene at the end of HĀ?

A: I don’t know how that came about, but I know when you hear dad’s voice telling him about how the fire is in you, it shows the audience has been following the young character since he was a small kid, and they know what’s happening right there. They realize he has a fire he can obtain, and the fire dancers at the end pass it on to him. Of course, others have different interpretations.

For me, personally, it’s a reminder we all have a fire within us. It might be a fire for different things. The viewer decides what he wants his fire to be. I want it to be something positive and uplifting, as a reminder to me.

Q: Who was the first director you worked under?

A: Jack Uale. I didn’t know much about him because I worked more closely with my supervisor, Tommy Taurima. He and Jack reported to Delsa Moe.

Tommy had been here for a while. I’m not sure how long, but he ended up moving back to New Zealand and got re-involved with Maori cultural education there. He had traveling groups that came here and performed. He was still very strict, but I never had a problem with it because I always just listened — perhaps because I was scared. Today, I find a lot of my style is because of the way he used to manage. When he saw a problem, he just called it out.

It’s a little different with the kids now. I have to be softer because they feel like, “Oh, you corrected me in front of everybody.” Back then, I never gave it a thought when in the middle Uncle Tommy would stop us and say, “David, you’re the only one moving this way, or this way.”

Yes, it was kind of embarrassing, but I didn’t take it personally. Tommy taught so many people here, I owe a lot to him. When I watched over the section, I did not have the title of cultural specialist because I was not Maori. I didn’t know enough, but I knew how to make the line maps. I knew who could do what, and who he and management would want in certain positions to assigned actions.

Q: Who took over after Uncle Tommy?

A: It took almost a year before they finally got the late Nihipora Wallace, who I look up to as well. We called her Auntie Nikki. She was really good, but Tommy was the one who made me think outside of the box. There’s more to it than just singing to a soundtrack, step out, and shine this spotlight there. Tommy was really good.

Q: Was there much difference among the various shows?

A: HĀ definitely was different, because all the shows beforehand were basically music-and-dance reviews.

This is Polynesia turned into Mana!, which turned into Horizons. Each one was different. Now it’s a storyline. That took a lot of convincing before we figured out, “What? We’re acting now?” But it made sense because Marketing did a survey showed the majority of visitors wanted “a very nice night show we wish we could understand what was happening.”

The community may not see it, but this is what people are coming to see. We’ve got to keep it going. This will make people come back. That’s how the Hā process came about.

When HĀ first started, there were just too many new things. I honestly did not enjoy it. I was cringing, worried about this and that. We had a new fire knife routine that involved six dancers.

One time the Maori kite fell apart. It flew over to Section Five where no one was sitting. Another time it flew into the audience and ricocheted off someone, but no one was hurt. And once it flew into the third row, which was empty. Within the first week, it didn’t come down. It was stuck. A stagehand climbed out on the catwalk to release it.

When HĀ was being created, we had to look at the core values in each of our cultural sections and the rest of Polynesia. When we realized at the end of the Maori section that the story was going to be told about this young man, Mana. Then we thought, “Okay. He’s celebrating life. In Tonga, his parents are welcomed to the village and Mana is born. It’s a birthday celebration.

In Aotearoa, he went from a little boy to a young man. In Samoa he falls in love with Lani. In Tahiti, they get married, and in Fiji, the young couple welcomed a baby but lose a grandfather.

In the Samoan section, sometimes I wish it was a mother-character playing the big brother role because some people don’t get it. Someone told me, “Oh, that was nice at the end when the boyfriend let her go.” No, that was her protective big brother.” If we put an older lady in that role, the audience might think she’s “an overprotective mom or grandmother.” Because I’ve heard it said so many times, however, I always respond, “That’s actually the brother.”

Q: Tell us about changing the coconut tree on stage?

A: The original one was getting too big, but the hard thing was we struggled to get a new tree onstage. First, it was too long, then we couldn’t figure out how to get it through the (stage-entrance) tunnel — without breaking fronds.

After we finally got it in the tunnel, we couldn’t get it up the steps on the stage. Maintenance brought in a tractor, but they only had a few older men to help; so we asked the young Tongan men who had just finished their “culture night” program at BYU–Hawaii for help. They said, “Oh yeah, bring it on.”

Q: Talk to me a bit about the costume department.

A: For a long time, a team of older ladies worked backstage making and maintaining Theater costumes. We called them “mamas” because they were like our mothers. We looked up to them, and they often fed us with what little they kept back there.

When Sonatane Falevai first came as part of our work-study program, he didn’t stand out. He couldn’t dance. Nothing. After he finally started dancing, someone said, “Oh, his brother used to dance here.”

“No way!” I said. He didn’t dance like the brother, but he had an impressive physique. True, he couldn’t dance very well at first, but he looked good. So, he got into the night show, and soon started standing out. When we held an audition for Mana, he came out. He was no longer the Tane we knew. He became Mana (the lead), and he was easy to work with — teachable, humble, and so good.

When Meet the Mormons 2 [a sequel to an earlier movie] approached us because he was being considered for the sequel, a production person said to me, “Tane told us he was not supposed to get hired. I want to interview you because he also told me he got hired because of you.”

“Yes, that’s right,” I said, remembering the audition panel asking, “What about that one?” I said, “He looks good. I think we can teach him.” He ended up being very good.

One time I told him, “Tane, I know you are on stage, but there’s a lady in a wheelchair who can’t walk down. Can you run up, take a quick picture, and come back down?” At the end, he ran up and told the lady, “I know you can’t come down, so I came up to you.” She smiled and took a picture.

Tane stayed here all four years. Even after he transferred to Marketing, he also held on here, until one day he said, “Lauren (his wife) needs to go to nursing school. It’s her turn now.”

With a big vacancy, we worked the role among the cast, but we knew many of them wouldn’t work out, so we opened auditions. Ricky Suaava took the role of Mana, and worked on Hā for about three years. He was not originally supposed to be the lead, but that person was involved with another job in Honolulu, so Ricky became our great, new Mana, and Hā moved on,

Q: Does anyone else stick out in your memory?

A: I will never forget when Donny Osmond was here with his son and the son’s wife’s parents, and I was giving him a tour. He understood all this because he’s a showman.

As we entered the stage, out of nowhere a shadow blinked past us. I looked at him, then heard a boom! The entire night show sail which is usually rolled up, had fallen — landing a foot away from him. His daughter-in-law jumped and screamed, but Donny just kept saying, “I’m sorry.”

I said, “No, I am so sorry.” He was a big thing for me as I was growing up, but that day he was so professional about the accident. He said, “Oh no, it happens.”

Another time, we sent the Promo Team to Branson, Missouri, and stayed for about six weeks. Branson is known as the home of good family shows. Merrill Osmond was there, and we would sit with our soundman in the sound booth. I asked him, “How long have you been doing this?”

“Oh, I’ve been doing this for over 30 years, working with different groups.”

“Who’s your favorite?” I asked.

He replied, “Do you know Donnie Osmond?”

“Yes, of course, I do.”

“I’ve never worked for someone so professional. That is the way he treats everyone,” he said.

Stevie Wonder, who we usually only see on stage, was another interesting visitor; but he didn’t want to be seen. We had him enter through the backstage drummers’ room. He sat in a drummer’s cave with them and waited. When it was time for the night show to begin, I got his helper to bring him out through the performer’s backstage tunnel, and as soon as the lights went out, we walked him to his seat.

His helper told Stevie, “Step out, slow, step down, walk straight, stand.” He sat in lower section one, which helped because of the way we had to bring him on, and also because he wanted to be near the percussions. Afterward, we all got excited when he came backstage.

Q: Is the Center your long-term career?

A: People joke and ask, “Are you still here?” And I answer, I have the best job because I see the night show kids come in and train, and end up graduating and leaving here better prepared.