Delsa Moe Expounds on the World Fire Knife Competition

The 2025 annual World Fire Knife Competition held on the Pacific Theatre stage at the Polynesian Cultural Center (PCC) was ablaze with dancers from around the world. The audience enthusiastically applauded and cheered the daring, warrior-like movements, the fierce fighting spirit of the contestants, and their skill with the lit weapons.

Indeed, this Samoan-inspired art form has captivated audiences for decades, ever since its inception as an organized event on the night show stage at the PCC in 1993. With powerful thrusts and throws, fire knife dancers wield the flaming knife known as the nifo ‘oti—a traditional Samoan weapon used in ancient warfare. This fearsome blade, with its curved, sharp hook, was literally named “the tooth of death.” Sometimes, it was made of sharpened boar’s tusks and added shark’s teeth on the bottom, compounding its lethality. These are real knives and real fire.

Mastering the art of the fire knife takes years of discipline and dedication. Competitors must demonstrate both authentic traditional moves and technical prowess. As Samoans laughingly like to say—quoting beloved Chief and emcee Kap Tafiti:

“We’re the only culture that gives a kid a knife and fire and tells them to go play.”

It’s been 32 years since Pulefano Galea‘i helped initiate the Fire Knife Competition on the grounds of the Polynesian Cultural Center. This year, fire knife competitors came from across the globe—Samoa, Tahiti, Japan, Australia, the Cook Islands, New Zealand, and more. Spectators tuned in from as far away as Israel and Egypt.

Interestingly, Kap’s words ring true in the case of this year’s men’s division winner, Hale Motuʻapuaka from Wahiawā, Oʻahu. Hale began training in Lāʻie when he was just 18 months old and first performed on stage at age three.

The 2025 World Fire Knife Competition winners were recently announced. In the men’s division, Hale Motuʻapuaka took first place, making him a four-time champion. In the women’s division, Moeatalagi Schwenke from Sydney, Australia, was crowned the winner.

Delsa Moe, Vice President of Cultural Presentations at the Polynesian Cultural Center, has been employed at the PCC for nearly five decades. Born and raised in Samoa, she moved to Lāʻie in 1978. Aside from a single semester in snowy Provo, Utah – where her one attempt at playing in the snow involved nothing more than a garbage bag and a hill – before returning to Oahu, the PCC and the warmth, movement, and energy of island life.

She’s remained rooted at the PCC ever since:

“PCC was the lure,” she says with a smile. “I enjoyed PCC more than I enjoyed college life.”

Delsa began her PCC journey as a demonstration guide 47 years ago in the Aotearoa (Māori) island village, before joining the theater department. She performed until graduation and was then hired full-time. She’s never looked back.

The Birth of the World Fire Knife Competition

Around 1992, then-President and CEO of the PCC Les Moore challenged his team to create new cultural events that would drive community engagement and revenue. At the time, the PCC was already hosting the Moanikeala Hula Festival. Delsa and others began to brainstorm additional ideas.

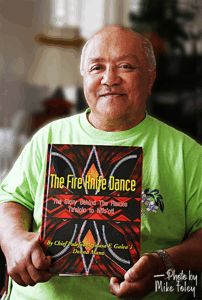

Pulefano Galea‘i, a long-time PCC visionary, had long dreamed of organizing a fire knife competition on a world-class level.

Alfred Grace, current PCC President and CEO, has often publicly reflected on the pioneers that built and improved this event:

“We drink from wells we have not dug.”

Of Pule, Delsa added:

“He dug deep and tirelessly to provide for future generations.

He loved entertaining and teaching. One thing he was passionate about was making sure fire knife dancers knew the origin and history of siva ailao afi—so it wouldn’t turn into just a fire baton routine. He would tell competitors, ‘You’re not a true fire knife dancer if you don’t know the history and traditional basic moves of the ailao afi.’”

At the same time, a local Samoan high school arts festival—previously run by O’Brien Eselu—had grown too large for one person to manage. This convergence of opportunity allowed Pule to propose that PCC take over the festival and launch the World Fire Knife Championship as part of it.

O’Brien Eselu (1955–2012) was a notable kumu hula and cultural visionary of Samoan heritage. Born August 12, 1955, and raised in ʻAiea, Hawaiʻi, he was a graduate of ʻAiea High School and the director of the Paradise Cove Lūʻau. A composer and choreographer across Hawaiian and contemporary styles, Eselu helped develop the “We Are Samoa” program at the PCC. He remains a cherished part of this legacy.

In 1993, the first Samoan Festival was held at PCC, incorporating both the high school arts festival and the new fire knife competition. At that time, it included only a men’s division, featuring mostly local performers. But word spread quickly, and the event gained prestige. New divisions were added—juniors, intermediates, women’s, duets, and group divisions—before settling into the current core of men’s, women’s, juniors, and intermediates.

A Cultural Mission in Motion

At its heart, the competition remains a cultural and educational mission:

“The goal of the high school festival,” Delsa says, “is to help students learn their culture, understand their identity, and appreciate their roots.”

While primarily Samoan, the event is inclusive, welcoming dancers from all backgrounds and fostering cross-cultural understanding—true to the PCC’s mission.

Though fire knife dancing as we know it today was popularized in the 1940s by Olo Letuli, its origins trace back to the ancient Samoan martial art of ailao, which featured the deadly nifo ‘oti. The hooked blade was once used in bygone battles to decapitate enemies and parade their heads as symbols of mana (power).

Fortunately, the influence of Christianity transformed this tradition into ceremonial performance. Letuli added fire for theatrical effect, but the foundational moves and meanings remain essential. “If we don’t educate dancers on the traditional moves,” Delsa cautions, “then it just becomes baton twirling with fire.”

Organization, Challenges, and Safety

Growing participation, especially in the junior and intermediate divisions, has led to logistical hurdles. A qualifying round in the men’s division was added this year to ensure performance quality:

“Some just want the glory of saying they competed,” she says, “regardless of skill.”

Judges are selected for their deep knowledge of the art form, ideally former or current performers. To ensure fairness, this year’s judging panel included judges from Lāʻie and other areas of Oahu and Maui; the other judges were flown in from across the globe.

Safety is non-negotiable. Dancers must stay within marked stage zones—at least 20 feet from the audience—per fire marshal regulations. Medical personnel are on standby, though no fire trucks are stationed onsite:

“Most competitors get burned, that’s expected” Delsa admits. “It’s part of the risk.”

Overall putting on the event is no easy task. Communication is an ongoing challenge:

“People just don’t take the time to read,” Delsa laughs. “All the information is on the website.”

A Global Stage

Thanks to live streaming, the competition now reaches viewers worldwide. However, PCC limits promotion of the livestream to preserve in-person ticket sales, which is vital to cover costs. Audiences pack the arena, especially during junior and intermediate nights when families come out in full force.

Looking ahead, Delsa and her team are evaluating ways to shorten late-night competitions—some run until 1 a.m.—and are considering creating a regional feeder system, where only winners of regional qualifying events earn the right to compete at PCC.

But one thing remains sacred: the PCC stage:

“That’s the draw,” Delsa says. “They want to say, ‘I danced on the Polynesian Cultural Center night show stage.’”

Personal Moments and Reflections

For Delsa, the most memorable moments are often personal. She tears up recalling when David Galea‘i, a local boy raised by a single mother working at PCC, won the world championship:

“It was like all of Lāʻie had won,” she says. “We were so happy for his mom.”

Another powerful memory: 15-year-old Melanie Lesoa winning the intermediate division—beating out the boys:

“When she spun her knife, the audience went crazy,” Delsa says. “It was historic—she was the pioneer for women in this competition.”

Melanie inspired a new generation, including Jeri Galea‘i, who went on to win the women’s championship twice.

Jeri Galea’i is crowned the women’s champion of the 2019 World Fireknife Competition

These victories go beyond trophies. They represent pride, community, and culture:

“Even though it’s a competition, that’s not the most important thing,” Delsa says. “It’s the sense of brotherhood, sisterhood, and respect for art. It’s about joy.”

Beneath the fire, athleticism and spinning blades lies something deeper: cultural pride, intergenerational legacy, and a community united in celebration.

These victories go beyond trophies. They represent pride, community, and legacy. “Even though it’s a competition, that’s not the most important thing,” Delsa says. “It’s the sense of brotherhood, sisterhood, and respect for art. It’s about joy.”

A Legacy Worth Preserving

Delsa is quick to honor the greats who came before. She again pays tribute to Olo Letuli, father of modern fire knife dancing, and Pulefano Galea‘i, the competition’s visionary founder. Their legacies live on in every spin, every flame, every cheer.

Beneath the fire, athleticism and spinning blades lies something deeper: cultural pride, intergenerational legacy, and a community united in celebration. As Delsa puts it regarding the Samoan way:

“We just like danger and excitement. And we like to have fun. And we hope others can relate to that spirit.”