test

By Sharla Behan

Flying Boat Journey: Matte Matina Te‘o’s Path of Faith

On March 8, 1960, twenty-two-year-old Matina “Matte” Te‘o boarded a Pan American Clipper alongside fifty-three other newly called labor missionaries from Sāmoa and Tonga. Their destination: the Church Building Mission in Hawai‘i—known then as Project Number Two – which would include work on The Church College of Hawaiʻi (now BYU Hawaiʻi), The Lāʻie Temple and finally the Polynesian Cultural Center. The 2,600-mile flight from Pago Pago, Sāmoa, to Honolulu marked the first time most of them had left their island homes, let alone flown on a plane.

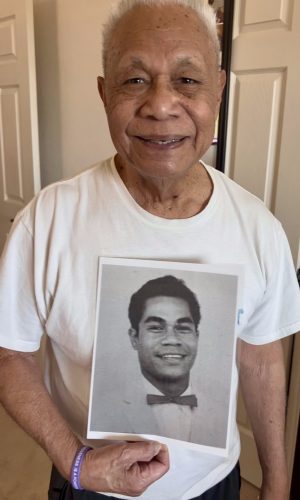

Matte is originally from the village of Vaiola, Savaiʻi, where his parents were serving at the Church school when he was born. He later moved to Upolu, in Western Sāmoa, specifically to the village of Sauniatu—meaning “prepare to go forth.” Now at the age of 88 and living at Lāʻie Point in Hawaiʻi, Brother Teʻo described the dreamlike experience from the vantage point of a “boy from the jungle.” He reflected on the memory of looking out the window of the airplane, or the “flying boat” as it ascended into the blue heavens of the Most High:

“I was in awe and amazed that it could keep all the people up in the air. I wondered how it would work—how could it lift all of us up? At first, I was scared. But the thought came into my mind that the Lord has His eye on me. When that thing started climbing into the air, I said, ‘How does this thing stay up? It’s heavy, full of people!’ Then I thought, ‘Well, that’s how much knowledge the Lord has given to us. He provided for mankind to advance in everything. You just trust it.’”

As the plane climbed, the young missionaries broke into spontaneous song—a familiar hymn they knew by heart that calmed their nerves and brought their minds back to the purpose of their journey:

“Oh, youth of the noble birthright—

Carry on, carry on, carry on!”

The harmony of their voices echoed throughout the cabin. Word came from the crew to please keep singing. With no movies or devices onboard in those times, the young men passed the time in singing and laughing.

After a refueling stop at Canton Island, a coral atoll in the Phoenix Islands of Kiribati, the flight encountered dangerous weather on their route. The pilot warned of turbulence and instructed passengers to fasten seatbelts. The missionaries bowed their heads in unified prayer. The pilot and crew witnessed something they had never experienced before: the dark clouds parted on either side of the plane as it passed through.

The group finally landed at Honolulu International Airport at 10:00 p.m. They were astonished to see the city of many buildings brightly lit against the dark night sky. After going through customs, they were greeted by leaders and finally boarded buses for the 40-mile drive to Lā‘ie and the Church College of Hawai‘i:

“There were so many lights! But on the drive to Lā‘ie, it was too dark to see much. We just kept winding along the road, heading to the barracks that would be our new home,” Matte said.

Miracle of Healing and Service

Before beginning his assignment in Hawai‘i, Matte had been serving as a building missionary in Sāmoa from 1958 to 1960. A skilled sheet metal worker from Sauniatu, he was still on assignment when the call came to serve as a labor missionary in Hawai‘i.

Then the accident happened.

While the workmen were tarring the chapel roof in Pesega, a bucket of tar caught fire. In an act of courage to save the chapel from burning, Matte quickly moved to throw the bucket off the roof—but suffered severe burns to both hands. After hearing the doctor’s prognosis, he was dismayed to learn he wouldn’t be able to go to Hawai‘i because of the severity of the damage. His shock intensified upon learning his charred left hand needed to be amputated:

“Is there nothing else that can be done?”

Priesthood brethren administered a blessing, promising healing. Matte recovered enough to attend the scheduled farewell program with his fellow missionaries. He then received further treatment at a hospital in American Samoa until he and the rest of the group departed for Hawai‘i.

On May 3, 1960, forty-seven labor missionaries – including Matte—participated in the largest single live endowment session ever held at the Lā‘ie Temple up to that time and received their temple ordinances. Matte prayed:

“Touch this hand. Fix this hand so I can help—whatever little bit I can.”

His hands, still healing upon arrival in Hawai‘i, eventually recovered completely with no permanent damage or scars:

“You just trusted,” he said.

And in the trusting, miracles came.

The Temple presidency recognized that the large number of labor missionaries were eager to do temple work after receiving their own temple blessings. Within a short time, a special late monthly temple session was created for them. Brother Te‘o was called to be a temple ordinance worker for this session and remembers hurrying to get to the temple on time:

“They opened the temple late for us because they knew we were going to come. So we do our building work and go home, take a refresh, run to the table, and then they (temple leaders) leave it open for us so we can come and do a session over there. That was very kind of them to do that.”

Working for the Lord: The Labor Missionaries of Lā‘ie

Long before construction began at the Polynesian Cultural Center (PCC), labor missionaries were hard at work transforming Lā‘ie. They built homes, renovated chapels, and expanded the Church College of Hawai‘i—now Brigham Young University–Hawai‘i.

In June 1960, crews began constructing a new residence for the temple president, along with four additional homes for temple guides. This project laid the foundation for the faculty housing effort on Moana Street, which would eventually result in fifteen completed homes.

Known as Project Number Two, the undertaking quickly grew in scope. In addition to dormitories and faculty residences, the missionaries built tennis courts, added a cafeteria annex, laid curbs, paved walkways, and enclosed the entire campus with a sturdy brick wall. Every building received a fresh coat of paint.

Their work extended to sacred spaces as well. Following plans designed by Church architect Harold W. Burton, labor missionaries made additions to the Lā‘ie Hawai‘i Temple. They tore down the old Bureau of Information and erected two tall structures on either side of a serene courtyard, complete with reflecting pools and colonnaded walkways—buildings that would later serve as the Visitors’ Center and the Family History Center.

And yet, their most ambitious task was still to come: the construction of the Polynesian Cultural Center itself, which began in early 1962 after its location was moved closer to Kamehameha Highway. Brother Te‘o recalled a quote from the labor missionary yearbook that captured the spirit of their work:

“When we build, let us think that we build forever—not for present delight, nor for present use alone. Let us think, as we labor, putting stone to stone, that someday our descendants will look upon these works and say, ‘See, this our fathers did for us.’”

“Yeah, I always remember that quote in the book, you know. It’s a beautiful quote.”

Ground Shift

Originally, the plan was to build the PCC near the temple. In fact, some land had already been cleared and underground pipes laid. The plan changed when Church leaders arrived from Salt Lake City and determined the proposed site was too close to the temple grounds.

But the new site had definite drawbacks. Matte recounted one of the major challenges:

“It was all swamp land. Water would run underneath it and keep springing up. They had to call in the brainy guys—the engineers—to figure out how to make the work easier and keep the water from coming back in.”

Much of the early work involved draining water and preparing the land.

“We’d dig, dig, dig with shovels. Then we started filling it up with shale and rocks brought down from the mountain.”

At the heart of the construction effort were moments of inspiration—both practical and spiritual. He recalled how Bill Kanahele, a Hawaiian labor missionary, came up with a clever solution while working on the lagoon:

“He said, ‘Let’s dig a perimeter around the lagoon first, pour the concrete and steel, and then dig the inside.’ It was very smart.”

Despite initial doubts, Matte marveled at how the land was transformed.

“I sat and thought about it later in my own little jungle-boy way, like, how can these people build on this? This thing’s going to sink!” he laughed. “But look at it now.”

Despite swampy land, frequent rain, and tight deadlines, the laborers moved forward with characteristic faith and determination.

In a moving recollection, Matte, one of the original builders of the Polynesian Cultural Center (PCC), shared his memories. .Each day brought a different assignment, and no task was too small. He and other labor missionaries rotated roles as needed.

“My part was to help with whatever labor there was. They assigned me to certain things and I concentrated on that part of the project. Then there was always something else waiting as soon as you’re finished. You know, at the same time we were building chapels over here.”

“So we have to, after our regular job—15 hours a day—go over there and continue building the chapels. Sometimes we finish at about one o’clock in the morning.”

“I say to myself, ‘Well, they threw their blood over there. It’s ready to go. What about you? You going to sit here and feel sorry for yourself?’ No. I got to put on my work clothes and get up. The thing is, once you get into that—your working clothes and that mood—the Spirit just comes and helps you. You know… just kicks things up. Right. Yeah.”

At the time, he didn’t know what would become of the project:

“Excuse me,” he said with a chuckle, “I didn’t even know the place was going to be for the public. I thought it was something else. Yeah, but then… you know, the Lord has a different viewpoint about things.”

Before a single shovel of earth was turned in the building of the PCC in Lā‘ie, Hawai‘i, the workers’ daily schedule began with faith. Matte would awaken at 4:00 a.m. and have personal scripture reading and prayer. Then the men in the dorm met to bow their heads, and finally the entire group of labor missionaries would gather in a circle around the flagpole:

“For PCC, we always start with a morning devotion. Every day, “We’d stand around in a circle and sing a hymn. Then our supervisor would say a few words—scripture-wise—and counsel us for the day. We’d thank the Lord for the beautiful day, because over here, most of the time it rains.”

Despite the constant exposure to unpredictable weather, the missionaries remained healthy and committed.

“None of us got sick because of the weather or the food,” he said. “We were called labor. That’s what we were—laborers. So we labored.”

Rain often delayed construction, especially during cement work. But the urgency of the project—and the sense of divine timing—quickly became clear to Brother Te‘o:

“It got to the point that we realized—no, I know—that our supervisors and leaders were inspired. You have to move on; otherwise, you’re going to fall way behind the schedule set by the First Presidency and the Church leadership. So, we worked rain or shine. We had to do it.”

When the first mission call ended, Elder Wilson offered the labor missionaries an honorable release.

“He said, ‘The project we were called to do—it’s not completed. If you want to extend your mission, it’s up to you.’”

Brother Te‘o chose to stay for another two years and completed two labor missions in Lā‘ie.

One Purpose, Many Hands

Construction was a community effort—no divisions among the people from different islands—built on teamwork and trust.

“We were all together in building the PCC,” he said. “The thing I really enjoyed was how everyone helped each other. They’d just call me, ‘Come over here,’ and I’d go.”

Though unfamiliar with certain tasks, the labor missionaries were quickly reassigned based on their strengths.

“I didn’t know how to do electric work, so they put me on air conditioning and general help. We always had a supervisor from the mainland who directed us.

Building the Vision

They began by constructing theaters and food areas, eventually building the individual villages.

“The first thing I remember was not the villages, but the theaters,” he said. “Then we started laying down the foundations for different villages and building the fales—the houses.”

As construction of the island villages began, he was assigned to work on the Samoan fales and a Fijian hut.

“I learned to love those Fijian brothers,” he said. “They were not members of the Church, but they volunteered to come up [to Lā‘ie]. They came with an idea that they’re building something for the Lord and that we’re going to be blessed. I was so close to them. They were very kind to me. They even gave me an honorary chief title.”

In time, Racule, one of his Fijian friends, joined the Church along with his family.

“He was so impressed by how things worked around here,” Tina recalled. “He was an inspiration to me, that man.”

Kūpuna Work: A Memory of Lā‘ie’s Grandmas and Grandpas

The old folks didn’t just sing—they worked with their hands, weaving and braiding sinnet from coconut fibers into strong cords for the building projects. Matte explains the process with admiration.

“You know,” Matte Te‘o, now age 88, begins with a warm smile, “all the old folks from Lā‘ie—the grandmas and the grandpas—come down. I like when they sit and weave stuff, and then they sing that song, you know?”

He pauses, remembering.

“Yeah, the song: ‘No toil, no labor fear… Come, come, ye Saints.’ Every single day I go over there, that’s the song they sing. I think that’s their theme song for the day while they make sinnet.”

“My job was to pound up the stuff—the husks—into little strings, you know? You gotta wet it, lay it in the water to soften it up. Then we bring it up and pound it down. Pound till it’s strong. After that, somebody else weaves it together.”

“The old folks from Lā‘ie did that,” Matte says. “Because they were more experienced. They knew how to do it right. Make it last long. Yes. It’s very touching for me, when I see them. And the grandmas, you know—they so… there’s something about them. They really moved me. They look old, so fragile… but they don’t quit. They just keep coming. Every day. Morning, noon, night. They outlast us young ones. Sometimes I think… I’m so glad the Lord made the Sabbath Day for rest—because these women, they don’t rest. No way. They are the first to come and the last to leave. Every single day. Early in the morning. Stay late into the evening. That’s why the work got done. Because of them. Because they just never stopped.”

Practical Matters

He recalled being shocked by his first encounter with American food.

“When they first told me they’re going to serve us dogs, I said, ‘Dogs?!’ But it was a hot dog. That was the first time I ever tasted hot dogs. I liked it. Even if it does not taste good, you say the blessing—the thing tastes good.”

“They gave us $10 a month—for toothpaste and toothbrush, and some health stuff. Otherwise, the Lord was prepared to take care of everything else. The sisters fixed our meals, washed our clothes, ironed, sewed, and mended everything. Then after that, we went by the place where they gave us our breakfast. And we say another prayer, you know—thank the Lord for the food and bless the kind sisters that come every time faithfully to take care of us.”

He learned many lessons during his service, but the hardest, he said, was “learning to humble myself.”

“Sometimes I kind of tell the Spirit what to do,” he admitted. “And then I catch myself. ‘Hey you, you’re nothing but a pile of dust.’ I ask for forgiveness. Just a silly kid from the jungle.”

Despite the long hours and challenges, he stayed faithful.

“Once you get into that mood, the Spirit just comes. Helps you. Just kicks things up.”

Final Thoughts

Matte never forgot the quote:

“See, this our fathers did for us.”

“I said, ‘If the Lord has something for you to do, help me do it good so I don’t go junk on the job.’”

He hoped others would feel the spirit of the PCC:

“It lifts you. Makes you light. You can’t frown in the PCC. Everyone smiles. There’s an aloha spirit. I hope that someone can benefit from what I’ve shared. If I err, that’s me; I’m human. But the truthfulness of the Gospel and the work of the Lord—nobody can change. It’s gonna stay forever.”

He ended his memories with sacred gratitude:

“President David O. McKay came to my village, Sauniatu, and blessed it. Still there today.”

From Sāmoa to Lā‘ie—Brother Matte Te‘o’s life bears quiet witness to faith, devotion, gospel in action. Still.

A Life of Service

Matte Te‘o married Gloria Jean Leina‘ala Kuuipo Byrd of Kohala, Hawai‘i. Together they have six daughters, one son (deceased), 12 grandchildren, and dozens of great-grandchildren. Brother Teʻo utilized the skills he learned on his missions to obtain a job at United Airlines, where he retired after 30 years of service. He served many years on the stake presidency, as a bishop, a temple ordinance worker and sealer in the Lā‘ie Hawai‘i Temple.

Your comment has been submitted for administrator approval.

Your comment was not saved. Please try again.

test

Comments

test