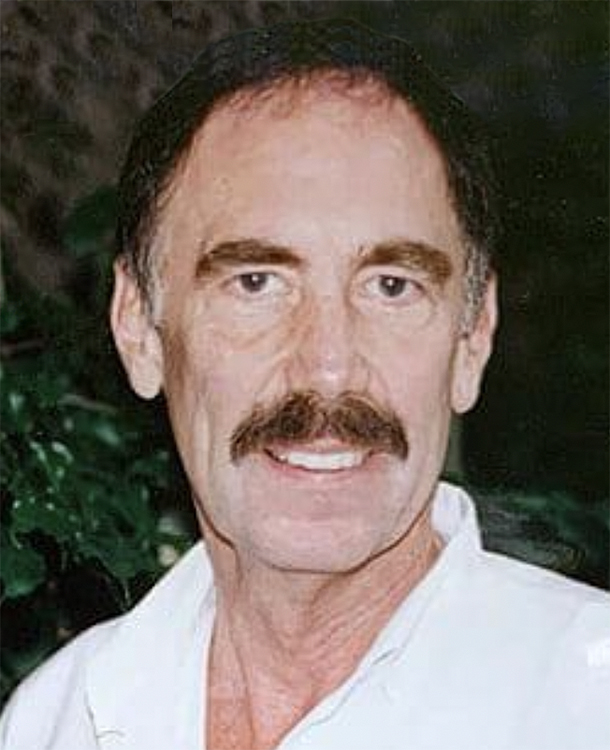

Larry G. Nielson, the Polynesian Cultural Center’s very first stage manager in what is now the Hale Aloha, brought an impressive list of talents with him when he became one of the PCC’s earliest employees in 1962. For example:

Nielson, who is originally from Ephraim, Utah (and now lives there), served as a missionary in Samoa as well as the Cook Islands, which in the mid-1950s was part of the Samoa Mission. Of course, he learned both languages.

His missionary traveling companion (by ship from and to San Francisco) was the late Ralph G. Rodgers, Jr., who later served on the Center’s board of directors, also as the creative show director, and then as PCC president and CEO in the mid-1980s.

In fact, Nielson was best man for Ralph and Joan Rodgers’ wedding.

He traveled the U.S., Europe, and the Orient as a singer and performer with BYU’s Program Bureau — the predecessor of the Provo school’s performing groups under the direction of Janie Thompson, and was also her assistant for a while. In fact, Nielson and Norm Nielsen, who later became a PCC management consultant, used to perform comedy numbers on BYU tours.

Nielson said after he graduated with a degree in art from BYU in 1962, “my dream was to get my master’s degree at the University of Hawaii, which didn’t happen, but I immediately got involved with the Church College of Hawaii” (CCH, which was renamed BYU–Hawaii in 1974). Because I already had my art degree, Wylie Swapp interviewed me and we became fast friends. I got a job teaching art classes.”

Because of Nielson’s RM background in the South Pacific and as a Program Bureau entertainer, he quickly became involved in Brother Swapp’s CCH Polynesian performing group, Hālau ‘Imi No’eau, which had already begun performing in Waikiki as Polynesian Panorama.

“That was a new direction for me,” he said. Similarly as part of his work at CCH, he got involved with (what was then called) “traveling assembly,” which performed around the neighbor islands, helping recruit local students.

At that time labor missionaries were working on what everybody still called the “Polynesian Village. The official name hadn’t been selected yet. It was then a lot of piles of dirt. The lagoon had been dug out, and I could see they were adding island structures and planting trees and foliage.”

Nielson also quickly established a close connection with Laie Stake President Edward L. Clissold, “whose young missionary companion in Hawaii in the 1930s became his best friend, [and the friend] eventually became the publisher of our local Ephraim, Utah newspaper. These connections are about networking. It’s not just luck, I also believe in synchronicity a lot. Wherever you go, you’re going to find somebody that you will connect with that you don’t expect.”

In Laie, for example, Nielson already had a strong connection with Howard B. Stone, one of his former mission presidents in Samoa. Stone headed Zions Securities, which similar to Hawaii Reserves, Inc. (HRI) managed non-ecclesiastical Church-affiliated property in Hawaii.

“The stage is set”: By the time labor missionaries completed the original PCC theater, Nielson said a consulting team from Hollywood had already become aware of his background in Polynesia and the arts. Michel “Mike” Grilikhes, an award-winning TV producer, and Jack Regas, who had a spectacular career in Hollywood as a choreographer and dancer with all the great MGM musicals and some of the biggest names, “invited me into the circle that became the theater at the Polynesian Cultural Center.”

Nielson said Regas was “a wonderful guy,” adding he supported and helped train him in technical theater aspects. Indeed, much of Nielsen’s work took place in the tech booth above the guest seats, “whereas before I was used to being on stage.”

He recalled some of the students he worked with “upstairs” in those early days included Gus Forsythe, a Samoan who had radio experience and got trained to work the sound board; Shishir Kumar, an Indian from Fiji by way of Liahona High School in Tonga, who also worked on sound and electronics; Warren Trueblood, a lights and tech pālangi who came from Liahona in Tonga, and many others.

Nielson fondly remembered working closely with the earliest Polynesian night show section leaders: Amani Magalei for the Samoans; Nancy Fine, Tongans and Tualau Vimahi; Isireli Racule, Fijians; Aunty Sally Wood Naluai, Hawaiians; and Erena Mapuhi, Tahitians.

He also singled out the late “mom” Christina Nauahi, a Hawaiian, for her work backstage handling all the costumes. “She was full of cheer, joy and support, and everybody adored her.”

Opening night: “We had such a huge crowd on opening night,” Nielson said. “That was the first time the audience saw the water curtain, and they were thrilled with the whole production. Every aspect of the show was professional and inspiring.”

“And after the premier, everybody was hugging, crying, and saying this was like a miracle to bring these nonprofessionals together and create such a beautiful experience. It was a dream come true.”

Other early PCC memories: “The whole format was totally unique, and we knew to be part of that the show was an incredible honor.” In those early opening days Nielson also remembered how the Hollywood “team” helped promote the Center by inviting movie industry friends to Laie, including Kirk Douglas, Tony Martin, Henry Fonda, Paul Weston, Joe Stafford, and Cyd Charisse, along with the governor of Hawaii and Church leaders.

Of course, “It wasn’t all glory. Almost everyone now knows in the early years after the initial excitement, we struggled with attendance,” Nielson continued; and a particularly indelible moment struck on November 22, 1963 — the day U.S. President John F. Kennedy was assassinated:

“That morning a lot of us were sitting in the audience seats, watching the Maoris rehearse, when it was announced over the loudspeaker that President Kennedy had been shot. I’ll never forget that moment of shock and silence. It was a very spiritual moment, where our natural instinct was to cry and pray for America and for the President.”

“On the stage, the Maoris began a tangi (for the dead), which increased everybody’s emotions. We all wept.”

Nielson shared another unforgettable experience one night after the night show with Elder Howard W. Hunter, then of the Quorum of the Twelve, the first president of the Polynesian Cultural Center and President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from 1994-95.

Elder Hunter, who was staying at the Laniloa Lodge during a PCC board meeting, asked Nielson, “When the PCC is closed, would you walk me around the Center and give me your side of this? Tell me how you feel about being here, because I’ve noticed you’ve bonded with the Polynesians.”

They met at midnight, and walked through the Center in the dark, talking of the Center’s mission and their own respective missions. “It felt like this was my dad talking to me, and it was one of the highlights of my life,” Nielson said. “It was just a stunning experience.”

His entertainment career takes off: After working in the PCC Theater department for about six years, during a mainland visit Nielson was asked to sing at Jack Regas’ daughter’s wedding, which led to “a completely new career.”

George Wyle, a major entertainment producer, musician and composer who was at the reception told him, “You got the kind of voice I want.” And he asked, “Well, you want to go on the road?” Jack [Regas] was standing next to me, and he said, “Yes, he does.”

Thus began Larry Nielson’s showbusiness career. “Wyle was producing the Danny Kaye Show on the road,” Nielson explained. “Danny Kaye was a big star at the time. He was doing a show in Vegas. And Wyle said, You got a job; and I was lucky enough to break in as one of his backup singers for that show.”

Nielson remembers going back to Laie and quitting his job at the PCC “with a lot of conflicting emotions.”

After performing at the Flamingo, Danny Kaye went on a national and Canadian tours, then back to Vegas, Arizona, and Tahoe; and after Danny Kaye, Nielson worked with Carol Burnett, Glen Campbell, and the Sonny and Cher shows, and on commercials. The Osmond family, who became close friends, invited me to go with them to Sweden for a full summer as their art tutor.”

While in Sweden, Nielson taught the Osmond Brothers Malie e, Tangifā — a Samoan chant about a shark and a whale, which they later recorded as a single in New Zealand.

“I was in the middle of show business, and I realized how lucky I was to have that one moment of opportunity. I didn’t have to spend a year or two auditioning for all these shows. I happened to be at the right place at the right time. That’s called synchronicity. It changed my life.”

An art career follows: Nielson added that when his show business career started winding down, “my art career took off very big.” He started doing a series of “funny animals” posters, several celebrity posters — including the Beatles, John Wayne, Janis Joplin, Jimmy Hendrix, Donny Osmond — and even black-velvet Polynesian paintings for galleries in Honolulu.

He currently focuses his art on what he calls his “Spirit of the Wood” paintings — all done on “old weathered wood” in Western, Native American, and Polynesian motifs. “President George W. Bush owns one, so does Liza Minelli, several others, and a commissioned portrait of Queen Sālote hangs in the palace in Nuku‘lofa.”

“It’s been a glorious experience so far, and it ain’t over.”

A profound blessing: Now, 60 years later, Nielson said “how thankful we were to be in on the beginnings of the Polynesian Cultural Center, and to get to know other cultures of the South Pacific. We found this a bonding force and blessing, and it was extraordinary.”

“We could feel a special spirit from the very beginning before the Center opened. Ours was a unique mission with a purpose. We started every rehearsal with a prayer backstage, as they do now. It affected us as individuals, profoundly.” “I made personal lifetime friendships that are still going on. Even now, we’re still in contact, and feel this bond of brotherhood and sisterhood that never could have happened any other way. I’ll be forever grateful for the experience, and I’m very blessed to have been a PCC pioneer.”